This semester, I've been struggling with the fact that I'm not a genius. No, not that I ever thought I was, but perhaps because I used to think that my worth was based on how much knowledge my cerebro could hold and how well I could apply it. I know, I know, that's dumb (irónico, ¿no?), but let's just say high school one semester (1,600 students), Lipscomb the next (< 3,000 students), Harding after that (< 4,000 students), and finally BYU (30,000 students) was a difficult series of transitions. I was one of the few girls in my foreign languages classes and everyone else had 2 years language experience in another country (a complete turn around from life outside of Provo). Before classes even started, for the first time, I was intimidated by my classmates (also, ALL the boys were on average 2-4 years older than me). I didn't meet a single male my age (20) my entire first year at BYU. 4 of my roommates were from Utah, and the 5th one had almost her entire family in the state. I made really cool friends, eventually, and I began adjusting to the idea that I wouldn't be moving after 3 months, but I also began this ridiculously self-destructive practice of believing that it mattered that my GPA (after a couple BYU semesters) wasn't as high as it used to be. I used to pride myself on grades, which isn't bad, but it's not good if you can't recognize other things that you are good at. And so, you can imagine how it felt when my computer crashed during finals week last week.

So, I'm not a genius. But I'm still smart. I've changed religions. But I still have faith. I'm not fluent in Spanish, but people can understand me and I can understand them. I can't dance very well, but I still have fun trying. And, I'm not the best. At anything, actually. But I'm good at a lot of things. And, so when I took a break from writing my 41 pages of final papers the last 2 weeks of this semester, this Pablo Neruda poem was just what I needed. I would like to invite anyone to read it any time they feel that their worth is dependent upon some kind of measurable success, because really, our worth is immeasurable. Book (or whatever it is you have become a slave to), when I close you, I open life.*

Ode to the Book by Pablo Neruda

When I close a book

I open life.

I hear

faltering cries

among harbours.

Copper ignots

slide down sand-pits

to Tocopilla.

Night time.

Among the islands

our ocean

throbs with fish,

touches the feet, the thighs,

the chalk ribs

of my country.

The whole of night

clings to its shores, by dawn

it wakes up singing

as if it had excited a guitar.

The ocean's surge is calling.

The wind

calls me

and Rodriguez calls,

and Jose Antonio--

I got a telegram

from the "Mine" Union

and the one I love

(whose name I won't let out)

expects me in Bucalemu.

No book has been able

to wrap me in paper,

to fill me up

with typography,

with heavenly imprints

or was ever able

to bind my eyes,

I come out of books to people orchards

with the hoarse family of my song,

to work the burning metals

or to eat smoked beef

by mountain firesides.

I love adventurous

books,

books of forest or snow,

depth or sky

but hate

the spider book

in which thought

has laid poisonous wires

to trap the juvenile

and circling fly.

Book, let me go.

I won't go clothed

in volumes,

I don't come out

of collected works,

my poems

have not eaten poems--

they devour

exciting happenings,

feed on rough weather,

and dig their food

out of earth and men.

I'm on my way

with dust in my shoes

free of mythology:

send books back to their shelves,

I'm going down into the streets.

I learned about life

from life itself,

love I learned in a single kiss

and could teach no one anything

except that I have lived

with something in common among men,

when fighting with them,

when saying all their say in my song.

*I would strongly recommend the original Spanish version to those capable of reading it. It's in the second person, which I think makes it more powerful.

Monday, December 20, 2010

Sunday, December 19, 2010

People Who Don't Look Like Me

I had an interesting conversation with a friend. After a quick, and probably unnecessary, spiel about differing opinions within my family about immigration and political reform, I was confronted with an uncomfortable question. For the sake of not getting awkwardly personal, I would like to pose the question to all readers (if there actually are any of you): How do our friends and family react to interracial relationships? I answered honestly and sadly that I don't think my family and I are on the same page. I couldn't decide which was sadder: having to say that people are prejudiced or knowing that others really believe there are benefits to a kind of subtle segregation between those who look like us and those who don't. I love that I live in a country where so many cultures are represented. I think interracial marriages are every bit as wonderful and loving as non-interracial ones. But the question was not about what I think: It was about how my social network feels.

Initially, I found this to be a valid question. A question of curiosity. Afterall, how one's family feels about certain circumstances would have some kind of effect on their life, right? But the more I thought about it, the less I liked the question. At the risk of sounding selfish or overly idealistic, or, horror of horrors, cliche, I would like to say that I don't give a darn. Yes, I am a product of my culture. I have been influenced by my community's, parents', and religion's beliefs. Perhaps I will never realize the extent to which I have been affected by these institutions. BUT I also have agency. I can make my own choices, and I don't have to subscribe to the beliefs of anyone or anything I disagree with. I'll date and marry who I want, because I know what I believe, and I know what I think is right. At the end of the day, I have to answer for my choices and my actions, not the opinions of someone else.

That being said, I would like to take a quick look at a problem that, I believe, is adding to the prejudism that needs to be overcome. Too often we say, "it's not going to matter in the next life, in 10 years, or even tomorrow." I have a better motto: "It doesn't matter." Period. That means now. If I were to tell my child (which I don't have one, yet, don't worry) that in Heaven it doesn't matter what color our skin is, and I leave it at that, what am I teaching? That the hardships and ethnocentric beliefs of the present are a harmless temporal reality? No! The fact is, the way things are today is not necessarily the way things should be. "The way things are" needs to be changed, and I can't change that if I resign to appeasing my social network for the sake of appeasing them. I'm sorry social network, but I will love and be as close to people who don't look like me as I want. I will be friends with immigrants, legal or illegal. I will hold hands with a boy that I like whether his native language is English or not. I will marry who I marry because I love them for the person they are and not their ethnic makeup.

To all those of you who tire of this subtle discrimination, I advise you to say something, because it matters today.

Initially, I found this to be a valid question. A question of curiosity. Afterall, how one's family feels about certain circumstances would have some kind of effect on their life, right? But the more I thought about it, the less I liked the question. At the risk of sounding selfish or overly idealistic, or, horror of horrors, cliche, I would like to say that I don't give a darn. Yes, I am a product of my culture. I have been influenced by my community's, parents', and religion's beliefs. Perhaps I will never realize the extent to which I have been affected by these institutions. BUT I also have agency. I can make my own choices, and I don't have to subscribe to the beliefs of anyone or anything I disagree with. I'll date and marry who I want, because I know what I believe, and I know what I think is right. At the end of the day, I have to answer for my choices and my actions, not the opinions of someone else.

That being said, I would like to take a quick look at a problem that, I believe, is adding to the prejudism that needs to be overcome. Too often we say, "it's not going to matter in the next life, in 10 years, or even tomorrow." I have a better motto: "It doesn't matter." Period. That means now. If I were to tell my child (which I don't have one, yet, don't worry) that in Heaven it doesn't matter what color our skin is, and I leave it at that, what am I teaching? That the hardships and ethnocentric beliefs of the present are a harmless temporal reality? No! The fact is, the way things are today is not necessarily the way things should be. "The way things are" needs to be changed, and I can't change that if I resign to appeasing my social network for the sake of appeasing them. I'm sorry social network, but I will love and be as close to people who don't look like me as I want. I will be friends with immigrants, legal or illegal. I will hold hands with a boy that I like whether his native language is English or not. I will marry who I marry because I love them for the person they are and not their ethnic makeup.

To all those of you who tire of this subtle discrimination, I advise you to say something, because it matters today.

Friday, November 12, 2010

Natalie's Manifesto for a New World Order

I had an EXCELLENT day today, I would just like to start out by saying. I felt alive while I was getting ready for classes, I was ON TIME for class, a girl I don't know stopped me and said she loved my coat, my historo-comparative linguistics professor coined the term The Schultheis Theory of Samoan Internal Reconstruction when the class spent 20 minutes unsuccessfully trying to disprove it, I saw a fantastic movie that received a standing ovation at Sundance (Under the Same Moon) followed by a Q and A with the film's writer and executive producer, I went to an international dance FOR WORK, and I decorated a Christmas tree. So, if my entry seems to be a bit gone with the wind, it's only because happiness is radiating out of me, which is probably why I was so motivated to write this in the first place.

Ok, so, after the Q and A, I took a break and sat in the Cougar Eat with my notebook and decided to do some much needed doodling. The doodling turned into listing, and the listing turned into a pros and cons list. Should I do the Peace Corps or Teach For America when I graduate? While I am interested in these programs because I do believe they are worthwhile ways to serve a community and because I believe I would enjoy them, I found myself writing in both columns, "law school prep." I stopped. Wait, do I wanna go to law school? "WHAT AM I DOING?"

Realizing my pros and cons list had been tainted, I started a fresh piece of paper and wrote what it is that I want to do. I self-indulgently entitled it My Manifesto:

My Manifesto

I want to help the world hurt a little less! Is that ok? I used to think this was ideal. Then I buried myself in literature last year that told me I would be naïve to make any statement remotely resembling Mother Teresa-y aspirations. So:

1. What's so wrong with being subject to such naivete to believe I can make the world a better place?

2. I'm not trying to be Mother Teresa.

3. So what if I was? Don't we need a few more people like her?

K, side-tracked, but the point, I believe, is to have lofty goals with a simple way of achieving them. So, I would like to propose a new world order to help the world hurt a little less by way of something I gained over the course of the last year and a half: empowerment. I was thinking about it a month or 2 ago, and I was trying to decide at what point I became resolute to come to BYU. Surely it would have been easier to just stay put (albeit, about 10x more expensive). That being said, I did not choose to switch to my 3rd school for a 3rd semester in a row to save money. I had always assumed I would graduate from college with an insane amount of debt, as most of my friends and family will, so it never occurred to me to seek a way to save more money, as embarrassing as this confession is. I didn't do it because BYU is a better school (although it most definitely is for someone with my academic interests). I just wanted to graduate and get on with life while I was at my second school, so why would I want to transfer AGAIN? Perhaps the most controversial reason that some may assume I came to BYU was for religious reasons. While these were undoubtedly tied, they are not what compelled me to make such great changes. I already had a great relationship with Jesus, so I did not look to coming to BYU as a way to be more religious, per se. So, now that I've said all the reasons why I didN'T come out to BYU, I think it's time to say why it is that I made the choice to change everything:

I wanted to do what I wanted to do.

Perhaps a bit vague, but let me explain. I was being helped through college, but the money I was receiving was a kind of tied aid. I could not worship where I wanted. I could not talk to certain friends if I wanted the money to keep coming in. Essentially, my source of payment for college was dependent upon my obedience to something that I morally objected to. I was not happy. I was not capable of making my own decisions. I was completely and totally dependent and mute should I continue subjecting to these terms. The opportunity to come to BYU was one in which I rejected the tied aid and became resolute to make my own future on my own terms. And I am doing that now. And I am happy now. The answer to why I did not continue to comply with my source's requirements is simply this: The lives we choose are better than the lives we settle for.

I propose that it is by independence and empowerment that the world will hurt a little less, just as I have been able to grow and become independent when I cut my own leash. I want to teach people that they don't have to accept a life that they do not wish for themselves simply because "that's the way things are." I want to see people doing what they want and what they know is right. I believe that only in a world where people do what they want can we hope to see a world that there people can find what they need on their own.

Saturday, October 2, 2010

Made In (insert 3rd world country here)

Not surprisingly, most of my clothes were made in developing nations, with the exception of a vast amount of Chinese-made products. Many items were from Bangladesh, Indonesia, Vietnam, Macau, Mexico, Guatemala, Malaysia, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Nicaragua, and Lesotho. Almost all of my T-shirts were made in El Salvador and Honduras.

Why?

Why is nothing we wear in the U.S. actually made here, and why is it all made in developing countries? I'm going to go out on a limb and say that American companies are outsourcing and exploiting the peoples of other nations for cheap labor. I see no worth in this. We get cheaper goods, but is it worth the price that we make someone else pay? Is it worth it to exploit workers for 12 hours a day just to that I can buy my low-priced t-shirts and running shoes? From what I can gather so far, it isn't.

I have heard many say say that these factories give people jobs that they wouldn't have otherwise. I spoke to a man who, when I argued that clothing made by a machine instead of hand woven goods exemplifies a loss of culture, asked me, "But what is culture? None of us have culture. We're globalizing and we're all the same." When I opened my mouth to argue, he told me, "Jesus never said, 'Be ye diverse.'"

Toucher. Toucher, mon amie. I never did read a scripture containing those words from The Savior. But, did He not teach us to treat one another equally? Are we not all children of the same divine heritage? Or, at the very least, are we not all human? Why is it okay for a Bangladeshi woman to work 12 hours a day in a sweatshop hemming the skirt I will buy in a JC Penny, but for a man to do the same job in the United States is inhumane? Do we have the same standards for someone without an American birth certificate? I asked this man if he thought these kind of jobs benefitted these countries. He told me yes, because they would have nothing else to do if we didn't bring them jobs. Hmm. I find this hard to believe. Would they not find something else to do? Some other way to create jobs? Personally, I don't feel like American factories in the developing world are really making much of a difference to their economies.

Friday, October 1, 2010

Knowing and Seeing

I did not get up and walk out of the movie cursing under my breath about bad taste. I was not offended. I do not even feel that it was a conscious decision I made to leave. My body just knew to grab my backpack and walk away while my brain tried to process the swollen influx of emotion that I had seen on the child's face as he opened his mouth to sob but never had the time to release the sound. Why couldn't I handle it? Except for my professor and his family who left when one of the 12-year-old friends of the protagonist who had been recruited was cursing them and threatening them with his gun, I was the only one who did not have the will to stay in my seat.

I have heard it said that some things are so horrible that you can't help but look at them. Stare. I think I understand that principal. I think that sometimes, though, things are 10 times worse, and you know that if you keep watching you will lose a part of your innocence or at least composure. I couldn't look anymore, because part of me didn't want for this story to be true. That's a lie. All of me wanted it to be untrue. I knew that over 75,000 of a nation of 5 million died. I knew that all boys were kidnapped at age 12 to join the national military. I knew that U.S. military personnel trained the national military. I knew that it was hell on Earth. I had just never seen it.

Seeing is different from knowing. Knowing is a list of facts. Knowing does not require empathy. Knowing allows us to create our own mental image of the situation. Knowing allows us to imagine the details to fit what is easiest for us to grasp. Seeing allows no such freedoms. Seeing is a direct transfer of a true image to my brain for internalization. Seeing is not flexible. Seeing questions my will to seek and accept truth. Seeing dares me to look and not act.

The El Salvadoran Civil War is over. I cannot use what I saw in Voces Inocentes to blog about the injustices that the campesinos are facing there. So what good are these haunting images in my mind? A tragedy that exists in our world today is that these movies are produced after the nations regain order. What genocides are being committed that I don't know about? Who needs our help now, and not 15 years from now when we are watching the traumatic experiences of the director on a big screen? Why make these films when the time is past? What did the director intend for me to be inspired to do?

There are several nations with child soldiers today. There is a drug war raging just a nation away. There is an AIDS epidemic ravaging life in Sub-Saharan Africa. There are girls being kidnapped and forced into sexual slavery in Southeast Asia. There are people taunting homosexuals so viciously in the United States that victims are ending their own lives. Is the face of a child entering into mortality enough to stop the world in its tracks. What have we done to the world we were given? Can we bring it back to the way it should be?

I came, I saw, now what?

Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Institutional Review Bourgeoisie, we dance again.

I'm back from Mexico, and I am possessed to return. No, really. I'm going back whether I want to or not (which, just for clarification, I do!). I'm undergoing the arduous process of analyzing my data from my study this summer and trying to compile some kind of comprehensible something that ends with some kind of tangible result. Pretty vague, huh? I blame my ambiguity on field studies.

Anyway, the purpose of this blog is to keep things "fresh" and "in the forefront" of my mind. My post-field writing professor is always telling me this, so why not give the advice of the university professor a try. Maybe he knows what he's talking about, eh? Consequently, this blog will serve as a pre-field journal as I dig deeper into the issues that interest me and strive to understand the gap in the literature I am delving into.

Right about now, you're asking, 'Natalie, just what IS it that you will be studying this time?' and I am so glad you asked. Actually, that's a lie. I'm not glad you asked. I don't know what I'm doing yet. I do however know what I like, so we'll start there (story of my life. No really.)

As I saw in my ranchos this summer, there were A LOT of migrant workers. I would have seen even more... if they weren't currently migrating. One former student found that 75% of the men from the area have migrated to the US at least once. I think migration is fascinating. I think the idea of uprooting oneself from everything they know and moving into a culture completely different from their own is an overwhelming task. Yet, these men do it as a means of income. Why? Why not depend on the government for money (more than some already do), or work in your brother's peanut fields, or sell at the market in the city, or go to school, or be a stay at home dad? I know that some of these questions would seem comical or even sarcastic if I were to ask them, but that doesn't make me any less interested in what their reasons and responses would be. Why Do You Migrate? There's opción número uno.

While we are still on the topic of migration, let's talk about the other idea I have a-brewin'. What about the ones who stay behind? What about the wives and children who depend on money from their spouse and father? The pregnant women who give birth and begin raising a child without the father? The women and oldest sons who must try to fill the hole that the breadwinner leaves behind? How do they adapt? Do they think it's worth the cost? I cannot imagine my mom sending my father off for an undetermined number of years and raising four kids alone. Then again, the people in these communities aren't as alone, maybe, as a woman could be in the United States. Extended families often live in the same village. Grandparents and aunts and uncles help look after their grandchildren, nieces, and nephews on a daily basis. Perhaps extended families step in to fill this gap when the man leaves. That would be interesting to ask about.

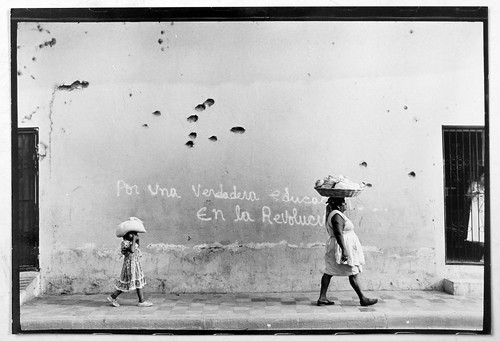

Lastly, I am greatly interested in literacy issues. Many of the older generations do not know how to read. Many mothers cannot help their children with their homework. My favorite student was very bright and I was surprised to find out that she was held back a year because of the difficulties she faced in learning to read. Her mother didn't know how to read. This is one example of how women's illiteracy issues transcend generations. I got to wondering if there were other ways that illiteracy among women affected younger generations. I began to wonder in what other ways illiteracy affected the women of these rural villages. I have NO idea.

And so, the field studies process begins yet again, and I find myself gearing up for another romp with the IRB (Institutional Review Board, or as I like to call it, the Institutional Review Bourgeoisie), an institution that exists to protect the human subjects I will be working with in my research. As I gear up to embark on another epic journey to rural Guanajuato, I would like to invite anyone who takes an interest in ethnographic and qualitative research, Mexico, migration studies, gender inequality, education, development, or me to share your thoughts and opinions as I blog away this school year (articles that you find would also be welcome and encouraged, and I can post them under my links).

¡Viva México! ¡Viva la igualdad! ¡Viva la gente que es diferente!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)